The body is the first altar and the first prison. It is the site of ecstasy and decay, divinity and shame, pleasure and terror. Every occult tradition has circled the paradox of flesh: is it sacred, a temple for the divine spark, or is it profane, a trap that chains spirit to matter? The answer is both — and that tension is the secret theology hidden in skin, blood, and bone.

Modern spirituality often sanitises the body. The wellness industry tells us to “love our bodies” with soft affirmations while simultaneously profiting from our insecurity. Religion, on the other hand, frequently treats flesh as a burden, a sinful husk to be controlled. The occult knows better: flesh is not a mistake but a mystery. It is the crucible where spirit and matter collide.

The Dual Doctrine of Flesh

Esoterically, flesh is both temple and trap because it contains contradictory truths.

As temple, it is consecrated matter. Breath animates blood, spirit rides nerves, ecstasy floods the nervous system. Mystics of every lineage — from Tantric yogis to Christian anchorites — have known that transcendence is not reached by abandoning the body but by entering it fully. Every shiver of pleasure, every contraction of pain, is liturgy.

As trap, the flesh binds spirit in hunger, fatigue, aging, decay. It tempts with desire, betrays with illness, and ultimately rots in the grave. No ascetic has ever denied this aspect. To be incarnate is to be limited, chained to a body that demands constant feeding and fails you in the end.

This paradox is not a contradiction but a mystery. Flesh is simultaneously the path to liberation and the reason we crave liberation.

The Occult History of Flesh

In Gnostic cosmologies, the body was often described as a prison built by the Demiurge — a cage of matter designed to entrap the divine spark. The soul longed to escape, to return to its celestial origin. Yet even within these dark mythologies, the body was still the gateway: gnosis could only be achieved while incarnate.

Alchemy encoded the same tension. The prima materia, often symbolised as the body, was seen as both corrupt and essential. Only by entering the putrefaction of matter could the philosopher’s stone be born. Flesh, in this light, was not rejected but refined.

Christian mysticism carried echoes of both poles. The body was described as “the temple of the Holy Spirit,” yet simultaneously warned as the site of temptation. Saints whipped their flesh to tame it, while also experiencing visions through its ecstasies. The contradictions reveal a truth: the body is never neutral in spiritual life. It is always the battlefield and the altar.

The Psychology of Flesh as Prison

Jungian psychology frames the body as both carrier of unconscious material and container of shadow. Trauma imprints itself somatically. The nervous system remembers what the conscious mind forgets. To many, this feels like entrapment: panic attacks, chronic pain, compulsions — all are ways the body holds us hostage.

This is the trap dimension. Flesh becomes the repository of ancestral fear, cultural shame, personal wounding. When religion speaks of “original sin,” psychology might translate it as inherited trauma encoded into the body itself. Escaping the trap requires not transcendence, but integration — entering the wound rather than fleeing it.

Flesh as Sacred Technology

On the other hand, mystics who embraced the body as temple found it to be the most direct instrument of the divine.

Tantric adepts spoke of kundalini rising through the spine, a serpentine current awakened by breath, sex, and ritual. The flesh itself was the temple where liberation occurred, not an obstacle to bypass.

Sufi mystics whirled until their bodies became instruments of transcendence. Christian mystics such as Teresa of Ávila described ecstasies that were not metaphors but somatic events — raptures that shook her to the core.

In occult ritual, the body becomes sigil. Gestures, dance, blood, breath — each action inscribes power into the field. The magician does not escape flesh; they weaponise it.

The Theology of Desire

Desire is where the paradox sharpens. Flesh craves: food, touch, climax, comfort. For centuries, religions condemned desire as proof of the body’s corruption. Yet desire is also the pulse of life itself. Without it, no creation, no continuity, no movement.

The occult does not deny desire; it transmutes it. Sexual alchemy turns lust into gnosis. Fasting turns hunger into clarity. Pain becomes sacrifice, ecstasy becomes prayer. The very cravings that “trap” us can be re-forged into offerings, sacraments, gateways.

Thus the body as trap and temple are not two states but two lenses. Desire enslaves when unconscious. Desire liberates when consecrated.

Death and the Rot of Flesh

Every theology of the body must face its most terrifying truth: it rots. Flesh decays. Bones bleach. Organs liquefy. This horror is why so many traditions treat flesh as profane. Yet occultists often approach death differently: decay itself is sacred teacher.

In necromantic practice, the corpse is not mere husk but portal. Meditations with skulls or graveyard vigils are not morbid affectations but acknowledgements that rot is revelation. To remember the body’s fragility is to wake from the trance of permanence. Death makes the flesh holy by reminding us that every moment is temporary, precious, already burning away.

The Trap as Necessary Initiation

Paradoxically, the “trap” is what makes liberation meaningful. Were the soul never bound, it would never know the hunger for transcendence. Incarnation is ordeal, but ordeal is initiation.

Think of the labyrinth: without walls, there is no journey. The flesh provides those walls. Every limitation, every scar, every failure of the body is part of the maze we must traverse. The trap is not punishment but curriculum.

Integrating Temple and Trap

The occult theology of flesh demands integration, not denial. To call the body only holy is to fall into naïve romanticism. To call it only corrupt is to fall into puritanical despair. The truth is both. Flesh is holy because it is temporary. It is trap because it is holy.

Integration means learning to live as if the body is both chalice and chain. Care for it as temple, knowing it houses the spark. Confront it as trap, knowing it will betray you with time. To hold both without collapsing into extremes is the essence of spiritual maturity.

Living the Theology of Flesh

What does this look like in practice?

- Treat your daily rituals as sacraments: eating, bathing, sex, movement. Approach them as offerings, not chores.

- Honour your scars and wounds as glyphs: they are the sigils of your lived initiation.

- Remember death in small ways: sit with impermanence so the body does not seduce you into denial.

- Use desire consciously: indulge not to numb but to awaken, abstain not to punish but to sharpen.

- Allow the body to teach you: every pleasure and pain is a scripture written in blood and nerve.

When you live this way, flesh ceases to be enemy or idol. It becomes paradox incarnate — temple and trap woven together in mystery.

The Body as Altar of Paradox

The occult theology of the body is not about choosing one narrative over another. It is about holding paradox as sacred. Flesh is the chalice of ecstasy and the prison of decay. It is both the site of bondage and the instrument of liberation.

To live in the body is to live in mystery. To reject it is to reject the path. To worship it uncritically is to fall into illusion. The true initiate learns to walk the razor’s edge: to bow before the body as temple, even as they accept its chains as trap.

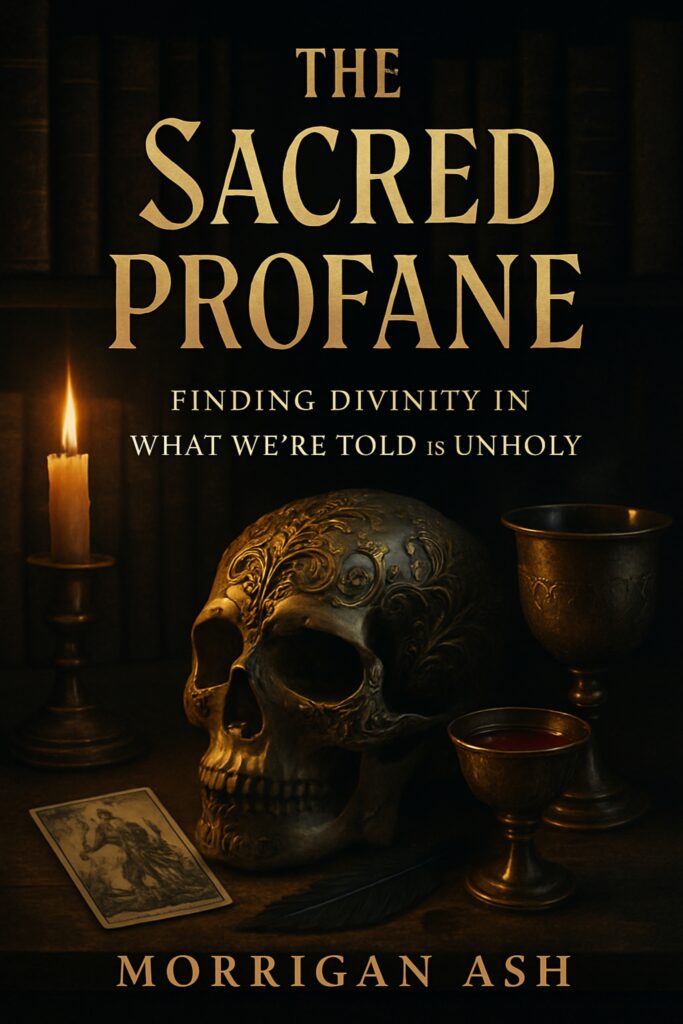

This is the teaching of The Sacred Profane: that holiness is not found by fleeing flesh, but by inhabiting it fully — rage, blood, sex, rot, and ecstasy alike. The divine does not fear the body. It hides inside it, waiting for you to open the door.